Dr Anjali Santhakumar

Consultant, Wythenshawe Hospital

My first NHS hospital

I was joining for my first clinical attachment in the NHS. I was walking into the unknown. I had trained and learnt my trade well in India. Pursuing higher training in UK, my first clinical attachment was on Western Isles – which according to a casual acquaintance at the time was the Britain of 50 years ago. I had no idea what Britain was like 50 years ago or at the time and remember thinking how this piece of information was useless for me! Information about the institution of NHS was more useful and it was described as THE place to work if you are doing medicine in the UK.

I arrived on Stornoway in a frightfully small aircraft, too close to the wide expanse of water for comfort. However with a population of around 6000 the airport transit would be the quickest I would ever know. I landed in what could only be described as freezing horizontal rain. I quickly realised this was going to be a constant feature and went to the one of few clothes shop on the island and purchased the thickest fleece lined jacket I could find. I wore this dreary beige jacket during the entirety of my initial 6 months stint as a clinical attaché and the subsequent 6 months I spent on this beautiful island as a senior house officer.

The hospital was small and welcoming; most of my patients had the same surname so that could be confusing or helpful depending on how you chose to see it. I was one of three or so junior medical doctors in the hospital. My circle of friends at the time on this island was made up of the hospital pharmacist, the podiatrist and the couple of doctors. In our spare time we took long walks and discovered the beautiful beaches and the open barren landscapes together. People we encountered on these trips were on occasions our patients later on. I learnt quickly that everything shuts down on the isles on Sundays. Our consultant on a rare occasion would give us a lift in his car to fetch groceries from the local shop after work, saving us all a few hundred steps.

I learnt to cook in the staff accommodation with other novice cooks and the local fire brigade used to respond to false fire alarms on a regular basis. The local joke was that the fire brigade didn’t rush if the call was from the local hospital staff quarters!

There were clinics on nearby islands where even smaller planes landed directly on the beach and bad weather meant an overnight stay.

I put my newly gained western styled communication skills, courtesy of the UK entry examination, to good use. As a clinical attaché, I matched my significant Indian medical experience with the more junior doctors who had relatively lesser clinical experience, (but with significantly more social and communication skills than I) and we made a good team. I learnt the nuances and vagaries of the local population and the NHS healthcare and slowly gained the trust and confidence of the senior medical team. I saw my first snow fall with a sense of wonder through the large clear windows of the medical ward here. I learnt how to winch down from a helicopter in case anyone on the local sea ferry needed medical attention.

Through all the hard work it slowly hit me that for the first time I was enjoying my medicine. I realised in amazement I was delivering classic textbook medical care. Treating patient with exactly the treatment recommended in the hefty medical textbooks I had to devour during my medical training.

I had spent part of my medical training in remote areas of rural India with limited resources trying to deliver best possible care but not always succeeding.

Here I was among unbridled amazing care, not burdened by costs, availability or affordability. What joy!

To the eyes of this young doctor, the NHS was amazing. In addition to the exemplary medical treatment, what particularly stood out was the high level of support the elderly were getting on the wards. The physiotherapy, the occupational therapy and the social resources available were truly splendid. The concept of getting patients’ home ready prior to their discharge was alien to me and I often wondered at the time whether the patients using the NHS realised just how lucky they were to be taken care of by this amazing institution.

I have now worked across an abundance of NHS hospitals progressing to an NHS consultant of many years standing now and I still think the NHS is amazing and THE place to work. I will always treasure memories of my first ever NHS hospital and would not have had it any other way. My only regret is that I did not attempt my driving test on this beautiful island with a single roundabout!

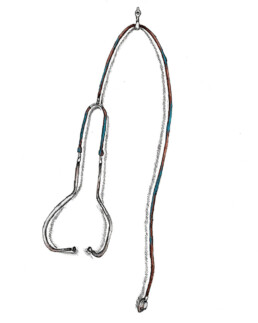

The Stethoscope

My old faithful stethoscope,

abandoned in the back seat of my car.

Once a lovely vibrant shade of blue I had chosen with delight –

now forlorn in an awful shade of red –

close to blood.

For years I trod purposefully

carrying this obnoxious thing.

A valuable tool working perfectly.

Ignoring for a long time

this frightful sight to behold.

The curious colleagues have asked me

and the polite patients have ignored it.

It is the polite ones,

the quiet ones

I wonder about.

Do they think I am a glorious warrior,

fighting COVID battles shedding blood, sweat and tears?

A true claimant to the uneasy hero cape we all wore?

My faithful ‘bloody’ stethoscope

a badge of honour?

I try to hold onto this glorious image in vain

But no,

they probably just think I am gross!

To the curious people who have asked me

Eeks.. is that blood?

I answer ‘No ! It’s crayons my children have had fun with

A perfectly reasonable answer

to people with kids.

To my closest confidante I spill the secret, alas!

It was a run-in with an open lipstick in my bag.

I can ignore this ugly thing

Around my neck no longer.

Sadly, my once perfect

faithful stethoscope now lies

disused and unloved.

Around my neck

lies a new stethoscope

in a fetching shade of purple.

Perhaps a new weapon

for battles unknown.

The Cardiac Arrest

“Adult Cardiac arrest in ward 24.” crackled the arrest bleep. A once familiar sound, now alien and intrusive, rang out loudly. It was the first day of the industrial strike by the junior doctors and I had volunteered to be part of the cardiac arrest team. I had come into work early, well prepared and wearing my flat comfy trainers – but had I come in with the mental preparedness and expertise I had taken for granted all those years ago…?

I had refreshed my training the previous day and commented that it was like riding a bike; it will all come back to me or…hang on…had someone else told me that?! Regardless it felt true. Questions remained. What role could I assume within the team? I decided I would be a follower rather than a leader today. Doubts if my injury prone shoulders could cope with the energy and vigour needed for cardiac compressions arose and then were quickly quelled.

“One hour to go before the shift ends.” This thought had barely crossed my mind when the darned bleep had blared out.

I raced down the long hospital corridor which seemed even longer than I remembered. I ran past a grey-haired lady walking casually along the corridor. She asked me, “Are you going for the arrest?”

“Yes.” I said as I ran past her. She picked up her pace and joined me and we ran in tandem, striding determinedly, strangers joined together in a common goal. We were nearing ward 24, a few more meters now and we were ready to save a life. Fuelled with adrenaline, we were ready for a flurry of action when the pager rang out again.

“Cardiac arrest in ward 24 has been cancelled”.

We stopped in our tracks. A mixture of relief and curiosity flowed through me and I looked at the lady beside me . We said nothing but I saw her emotions mirrored mine. Beaten in our valiant efforts to save a life, we turned back and trudged back together along the same corridor. “Nice running with you”, I shot out when we parted ways. I returned to my base ward feeling free to audibly pant, now that I was no longer with my composed running partner.

I went back to my ward, returning to smiles from staff who were delighted to see me back so quickly. My unknown patient lives to see another day I thought. I could not help being curious – would our efforts have made a difference to him? For some strange reason I was certain it was a him! Would me and my shoulders have come through for him? I will never know.

I remember

The first time I got paid

for being a real doctor

I bought myself a CD player,

my dad a shirt

and my mum a dress

The exultation and elation

at passing my exams,

following a truly

fearful moment

before I glanced at the result.

The first patient

who died suddenly –

the sorrow I shared

and the tears I shed

for the family.

The first time I walked

miles across rural India,

across hills and streams

to vaccinate a child

in a remote primary school.

The first time my patient

asked if I’d had a chance

to eat and rest –

the affection and gratitude

I felt towards him.

The brave families

I have talked with

about frailty and loss,

about hope and despair

and all things in between

The first time I put on my PPE

for my first covid patient

with nothing to offer but oxygen and words.

And then the last time

with an armful of drugs to help.

The many hospitals and teams

I have worked with

across the UK and India –

the camaraderie and the laughter.

The differences and the likeness.

Illustration: Lucy Waterworth