Anna Jerram

Vascular Scientist

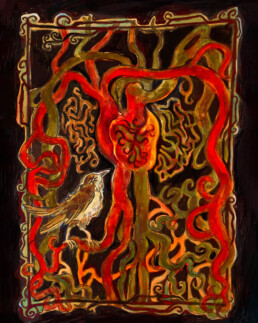

Ebb and Flow

It was July 2004. A memory inked so vividly, it feels like it happened just yesterday. Passing through the painfully-slow-to-open automatic entrance doors of Manchester Royal Infirmary for the first time; the gateway to what was to be not only a new job, but my career: A tiny, yet integral brushstroke. My small (but not insignificant) mark to make, on the vast, diverse, and colourful canvas of the NHS – then 56 years in the painting.

Following the otherwise featureless, shiny-floored maze of corridors through the hospital, a porter smiled and nodded at me with a look of misplaced recognition. I had served him his hard-earned after-work pint only months before, in my former role as a part-time student bartender at the pub on the corner, which joined the sprawling hospital site to the bustling campus of The University of Manchester. The corner I’d turned just that morning, between my recent past as a struggling and disillusioned biology student at the very same university, to my imminent future as a trainee Vascular Scientist.

I had never heard of a Vascular Scientist before I inadvertently stumbled across an advert in a jobseekers’ newspaper; brought home by my partner who conveniently worked in a job centre at the time. It was a moment that felt like fate, but was probably just jolly good timing. I was nearing my final year exams, and the prospect of the void which lay beyond them loomed all too uncomfortably close. My love affair with all things science related – which had blazed hotter than the blue flame of a Bunsen burner throughout my secondary school and college years – had dwindled to a barely glowing ember in the midst of my university experience. I was burnt out and depressed, convinced that I’d fall at the final hurdle, with no inkling of my direction in life for the very first time. Up to that point, everything had seemed so mapped out. Now, I just felt lost.

Something about that job advert spoke to me. I felt strangely excited about something for the first time in a long time. Maybe it was just the slim possibility that the hard slog of a degree I’d fought my way through might finally be for something – a possible passport to my next destination. But it sounded like a job that might suit me. Or maybe more so, that I might suit it. I had always felt drawn to a career in healthcare. I’d toyed with the idea of studying medicine for a while, then talked myself out of it at the peak of a teenage confidence crisis. My high school work experience placements had been in a pharmacy and a hospital radiography department, and I had volunteered as a care assistant at a local care home for the elderly and in the Lourdes pilgrimage hospitals.

I knew it was a long shot to apply, possibly bordering on cheeky: I hadn’t even got my degree yet. But I had nothing to lose and potentially something substantial to gain. So, I hurriedly filled in the application form and popped it in the post box, before I had time to talk myself out of that, too. Raised in a Catholic church-going family, I found my relationship with faith and religion confused and conflicted throughout my turbulent teenage years. So, it tickled me to find myself praying that I would at least get an interview. As the spoilers above might suggest, my prayers were answered: I did get an interview and, to my disbelief, I was offered the job on the basis that I passed my exams, and my degree was in the bag. And that was just the push I needed to get across the finish line. I got my degree, somehow, and the next chapter of my journey was about to begin.

Tentatively pushing open the door marked ‘Vascular Laboratory’, I was unknowingly stepping into the department in which I was to spend the best part of my working life, eventually splitting my time between Manchester Royal Infirmary and Trafford General Hospital. A tidal wave of imposter syndrome crashed over me, just like it had on my first day of primary school. Mum’s comical recollection of my meltdown that morning, when I proclaimed that I couldn’t possibly go in because I ‘couldn’t read, couldn’t write, and couldn’t play netball’, was suddenly in full re-enactment beneath my deceptively calm exterior. Thankfully by this point, I could read and write (netball skills remained dubious), but I didn’t have the foggiest idea about how to do a vascular ultrasound scan.

Flashbacks of the faulty flicker from an old X-ray lightbox on the wall. Long-sleeved, trailing, unhygienic white lab coats, long since outlawed by hospital infection control policy. The steady, rhythmic beat of a patient’s pulse drumming through the door of a nearby clinic room. All irrevocably etched on my anxious whirring, stirring mind that first day. The first of many days, which came and went in a flurry of unfamiliar faces, places, skills, and concepts to quickly learn and remember. As I apprehensively opened the textbooks to get better acquainted with this new-fangled field, tongue-twisting terminology came at me thick and fast: the foreign dialect of vascular science and surgery. And quite unexpectedly, somewhere in the learning of this new language; along the path to making vascular feel vernacular, I felt fuel on the dying fire. A reignition of my interest in science, and the confidence to study again, sparked at the coalface of a healthcare profession which felt vocational.

Sights and smells I had never imagined possible would now be encountered daily, as I progressed through the training program to perform and perfect the art of the vascular ultrasound scan. Sick bowls and stoma bags; leg ulcers and gangrene. Blackened, bloated, oxygen-starved toes; the result of a blood supply so narrowed and blocked, it was beyond the point of repair with the plumbing attempts of even the best vascular surgeon. With a stench so extreme you could taste it: the acerbic smack of putrefying flesh. I was taught the trick of a subtle slick of vapour rub, dabbed in the groove between the nose and mouth: a welcome remedy to this repugnant fug (which enabled the illusion of unfaltering professionalism) – its acrid top notes mellowed by the menthol. My childish aversion to this overwhelming olfactory assault would be quickly quashed, however, by the dawning realisation that this poor patient was suffering silently in a world of pain so agonising, any brief discomfort of mine was squished to a scant speck on the distant horizon.

The heart-breaking, humbling experience of working each and every day with people in pain had a profound effect on me. It was a jolt into gaining some perspective on my own worries and problems, and awakened me to the harsh home truth that I still had a fair bit of growing up to do. In my last job, the worst case scenario was that I served an unsatisfactory pint to a disgruntled customer. Now, the diagnostic test results I reported would signpost the course of a patient’s treatment, potentially leading to major surgery or lifelong medication with some serious side effects. It would take me a while to acclimatise to this new level of instilled trust and responsibility. There were times when I wobbled and doubted my ability to see the course through to completion. But I persevered, and in 2007 I passed my postgraduate exams to become an Accredited Vascular Scientist.

The learning never really ends though, in a workplace where every patient presents with a different lesson to teach you. From seldom seen pathology to bamboozle the brain of even the most experienced practitioner, to a tale of triumph over seemingly impossible adversity which enkindles a new way to look at life. Patients from all backgrounds who had survived earth-shattering episodes: cancer diagnoses, blood clots, heart attacks, strokes and organ failure to name but a few. People who were quite literally facing the prospect of the loss of life or limb, despite the best efforts of the medics and surgeons to salvage both. Perhaps the most inspiring of all were the patients who did indeed lose a limb, but were still living a life, after months of arduous amputee rehabilitation.

Nineteen years on – almost half my lifetime – and I’m still learning. Perhaps the most elaborate lesson of recent years was how to make it through the days that came under the dark dictatorship of Covid-19. The memory of those first months still has a dream-like quality. Hospital corridors once alive with human traffic, were eerie and echoing. Haunted by the ghosts of porters pushing patients in wheelchairs and beds, back-and-forth between appointments and departments, staff hurrying and scurrying to clinics and consultations; friends and families stopping to ask for directions, on the way to visit their loved ones.

By that point in my career, I felt I could tackle most situations quite well under pressure. I’d learnt not to sweat the small stuff. But working on the Covid wards during that pre-vaccine period was a whole different ball game. It felt big, and I was sweating, profusely. Wrapped head-to-toe in plastic PPE in that sweltering, machine-crammed corral, trying to interpret a diagnostic ultrasound through the fog of a steamed-up safety visor. Convinced that the edges of my well-fitting mask were warping; welcoming unwanted, invisible, airborne invaders into the stream of my stifled, shallow breath. And I had it easy. At least I got to leave the ward once my job there was done; free to breathe more easily out on the cool, deserted corridor and return safely back to base. How the staff confined to the care of the patients on those wards endured those dreadful, demoralising days; my mind still boggles.

Post-pandemic, and the deluge of destruction this virus brought to pass continues to ripple through the undercurrents of daily life in the NHS, as it approaches its 75th year. The undying devastation of lives lost; the melancholy memento of long Covid, still loitering by those unlucky enough to be lumbered with it. Cancelled appointments, procedures and delayed life-changing treatments; the consequences of which are still unfolding.

In the years since I started as a flustered, fledgling trainee, there have been many changes. Colleagues have come and gone; some moving on to pastures new. Others stayed, as assuring and supportive as they were on that first day. Patients came and went too, most returning home after fighting their way to a full recovery. Others sadly lost their battle.

The entrance doors of the hospital still don’t open fast enough, and the X-ray box still flickers on the wall above the desk. Otherwise, the hospital site as I knew it in those early days has transformed almost beyond recognition; restructured, merged and developed to meet the ever-increasing demands of a growing and ageing patient population.

As for me, I find that I don’t rely on the vapour rub trick quite as much to do my job anymore – nose hairs and taste buds desensitised by countless gruesome gangrene exposures. Thankfully, the heart-felt emotions which invariably arise for the patients I’m entrusted with the honour of caring for, remain yet to be hardened.

Illustration by Maria Hallewell-Pearson